Caught between ideals and influence: Traoré faces the angel of Thomas Sankara’s legacy and the devil of Vladimir Putin’s power. Illustration by Herbert Joey Mirasol.

It all began with a coup…

Years ago, in the midst of a late-night Wiki-spiral, the phenomenon that ignites niche interests and ‘click-and-run’ tidbits of information ripe for pub trivia, I came across an article detailing history’s youngest serving state leaders. Sifting through its various lists, I fixed my gaze on the one itemizing the world’s ten youngest currently serving state leaders, featuring the likes of Chile’s Gabriel Boric and Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman. But what particularly seized me was the image of a young man who ranked second on the list, who in his Wikipedia photo masked a flinty stare, wore a red beret, and donned green military fatigues with proud fortitude. His gaze was unyielding, his portrait radiating gritty optimism and cautious sparks of hope for the country he would preside over, Burkina Faso, which he had only begun serving at the age of 34. This man was Ibrahim Traoré, an ambitious soldier turned lieutenant who would later be hailed as one of Africa’s most popular leaders of the 2020s. Born in Kera, Bondokuy, Traoré would later fight in the Mali War in 2014 before returning to his native Burkina Faso to combat the rising Islamist insurgency, comprising Al-Qaeda’s JNIM and Islamic State’s ISSP. He was soon promoted to captain of the Burkinabé Armed Forces in 2020. Rising through the ranks, the “quiet” but “talented” geology graduate would become disillusioned with the governance of then-leader Paul-Henry Sandaogo Damiba and would eventually overthrow him on 30 September 2022, buckling himself onto West Africa’s ever-tightening “Coup Belt” (yet another intriguing Wiki-spiral for the geopolitically-inclined).

Traoré’s brief biography seemed a page right out of the regime change playbook. Another derivative retelling of disgruntled military officers with a Napoleon complex, vulturing foreign powers draped in white, blue, and red, and frantic shouts for a new town sheriff. Nonetheless, I was excited at the prospect of Traoré and what he could achieve for a nation that, as of 2025, has been the world’s most impacted by terrorism. This could be the man to stabilize Burkina Faso’s precarious state, weaving it back together with pragmatic martial values combined with young Pan-African idealism and a touch of Marxism. No more corrupt career politicians stealing money from the poor, no more strongman military veterans with a lust for warmongering — but at last, a new leader re-imagined for the digital age who fits nicely into the legacy jeans of Thomas Sankara.

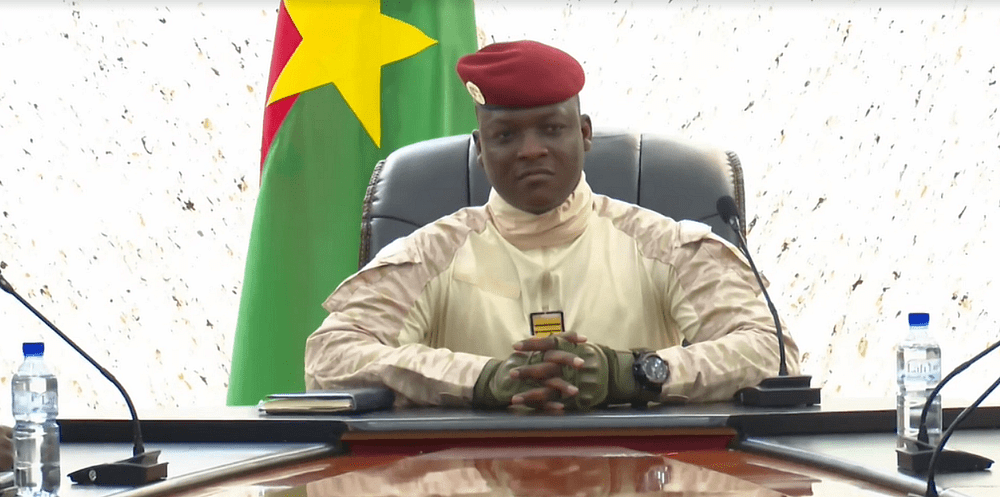

Grounded in governance: Ibrahim Traoré attends a meeting in Ouagadougou, July 2023. Photo by Lamine Traoré for Voice of America.

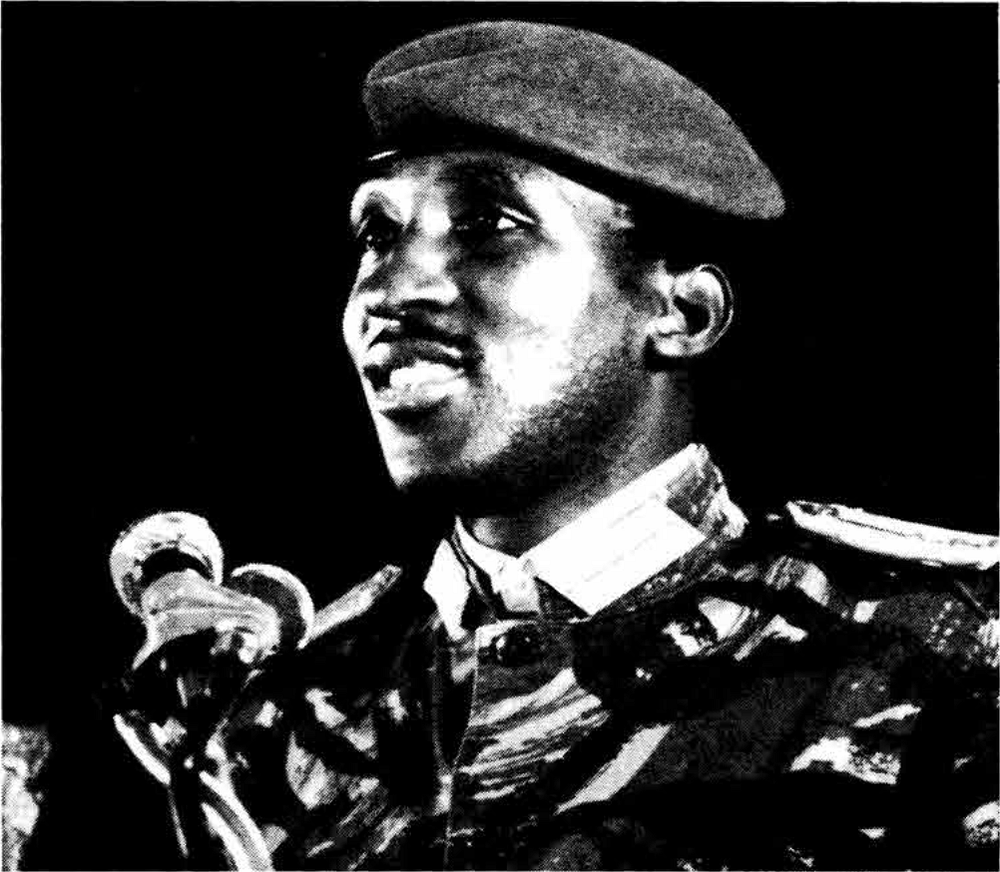

The imprint of the Pan-African Marxist revolutionary — once dubbed West Africa’s answer to ‘Che Guevara’ — would always be a looming shadow of comparison with any Burkinabé leader thereafter. After seizing power in the 1983 coup d’état, Thomas Sankara emerged as a remarkable leader whose words inspired hope and courage among his people. Having read and fallen in love with his oeuvre of speeches in the book “Thomas Sankara Speaks” (1998), I, too, was enchanted by the Burkinabé leader’s devotion to his country’s prosperity — a devotion expressed poetically through the addresses he delivered both on the world stage and at the grassroots level. However, it was not just his words that garnered appreciation — his actions, too, would come to be held in the same esteem. For example, in 1983, Sankara encouraged collective farming and boosted local goods production by launching major agrarian reforms, redistributing land to farmers. In 1984, he implemented public health and reforestation campaigns by planting millions of trees to deter desertification, and vaccinating over 2.5 million children from preventable illnesses. Sankara also advocated for gender equality, appointing women to governmental and military positions while outlawing female genital mutilation. He even changed the country’s colonial-era name from “Upper Volta” to “Burkina Faso,” words derived from the Moore and Dyula languages, meaning ‘land of upright or honest people’. Unfortunately, his death (and tragic betrayal reminiscent of a Shakespeare play) would exacerbate the country’s ingrained socio-political issues and instabilities, sowing the seeds for the impending insurgency that would affect most facets of the country in the present day.

Jumping back to September 30, 2022, suddenly the country’s woes felt closer to absolution. Anchored by his dark charisma, Traoré and his military junta —the Mouvement patriotique pour la sauvegarde et la restauration (MPSR) — were met with popular support (albeit with some skeptical detractors) as he pledged to rectify the security concerns of Damiba’s government, stated his desire to “lift [Burkinabé] people out of this misery, this underdevelopment, this insecurity,” and promised civilians a democratic government. As a result, for three years, I checked in on Traoré, watching his profile grow as his voice echoed more and more across international media. And for three years, I turned to local Burkinabé news channels broadcasting Traoré’s commanding and arresting speeches addressed to the nation, equipped with a charming smile and a penchant for fist bumping in lieu of the outdated handshake. For those three years, it seemed Ibrahim Traoré’s emergent and juvenile energy was winning the hearts and minds of Burkina Faso and regions both digital and physical across Africa and beyond. But now, as his presidency ticks over its third year, my once-idyllic image of Traoré has faltered — dramatically, to say the least. Reflecting on my past veneration of “the 21st-century Sankara,” I find myself confronting the many contradictions, controversies, and challenges I had been willing to overlook and justify in believing that Traoré could truly become Burkina Faso’s new revolutionary leader. Needless to say, it left me much to ponder about.

Oversights, justifications, and truths

And in that pondering, I’ve deduced that Traoré has disappointed, devastated, and deceived, not just my opinion of him, but in tangible ways — through actions that most certainly have endangered civilians, undermined democratic institutions, and led to ill-fitting political relationships. The best way to evaluate this is by listing some of the questionable acts and decisions of Traoré I was willing to bypass during his presidency, followed by my retrospectively naive explanations as to why I was willing to overlook them in the first place. These justifications I told myself and other people (‘Of course Western media will say that!’, ‘Let’s just see what happens’) will reveal just how blind I was to the troubling realities of Traoré’s rule and how easily persuaded one can be by his charismatically manufactured persona. Consequently, as noted in the final category, I would overlook certain truths I was too ignorant to consider and confront at the time: a myriad of injustices imposed on the Burkinabé people, betrayals to optimistic digital citizens desperate for a revamped African freedom fighter, and hints of regressing into badder times devoid of Sankara’s magnetism.

Oversight 1: The way in which Ibrahim Traoré seized power.

Justification: I was willing to overlook Traoré’s unconstitutional rise to power because, despite its illegality, he framed his coup as morally and politically legitimate, citing the previous government’s failures in security. At his inaugural address in October 2022, Traoré stated,“Of course, we can all see the deteriorating security and humanitarian situation in which our nation was living. This is what led us last January to take unconstitutional action to restore and revive this nation.” At the time, those words resonated with me, and I believed that this coup was less an unlawful power grab and more an authentic declaration for serious change. Additionally, Traoré’s swift and bloodless overthrow was immediately popular among the Burkinabé people. It offered premature but positive indications of a new moral leadership that could steer the nation away from its violent predecessors. For instance, instead of imprisoning him, Traoré and his junta brokered a deal with Damiba following their victory, allowing him to go into exile in Togo without facing further punishment; in 2024, he granted “amnesty” to 21 soldiers involved in a failed coup in 2015, showing a willingness to forgive.

Furthermore, Traoré’s rhetoric and persona echoed that of Thomas Sankara, marked by phrases like “La patrie ou la mort, nous vaincrons,” his military uniform, and the iconic red beret. This resemblance to Sankara has left many nostalgic, jogging their memories of a time spent changing the country for the better. Similar to Traoré, Sankara morally justified his coup by expressing dissatisfaction with the ruling government and a commitment to leading the Burkinabé people out of hardship. He proclaimed, “The triumph of the August revolution is due not only to the revolutionary blow struck against the sacrosanct reactionary alliance of May 17, 1983. It is also the product of the Voltaic people’s struggle against their long-standing enemies”. If Sankara could assume power, albeit illegally, and commit to helping his people, why couldn’t Traoré do the same?

Inspiring change abroad: Thomas Sankara delivers a speech in Harlem, New York, 1984. Photo by Ernest Harsch.

Truth: Upon reflection, allowing Traoré to break the law in his ascent to power undoubtedly spells trouble for the remainder of his presidency — and beginning what is meant to be a new and virtuous leadership with multiple treaty violations is certainly bad politics. It’s like the old saying about relationships: they end how they begin. You might ask, “What if the coup was the only way to take down Damiba, the bad, and replace him with Traoré, the good?” That’s a fair question. To that, I would reply, “Then why doesn’t Traoré relinquish his position and let the people vote for their leader freely and fairly?” When Traoré seized power, he pledged to restore civilian government from military rule by July 1, 2024, promising to hold free and democratic elections. However, this promise was discarded when, in 2023, he stated that democratic elections were “not a priority” for the country and instead insisted that“[Burkinabé] must ensure security first,” a matter for which Traoré and his junta have faced criticism forlacking adequate political strategies, overly relying on foreign military support, and maintaining a lack of transparency in military operations.

In fact, Traoré holds negative views about democracy, stating, “When we cite a single country that has developed through democracy, it is not possible,” and asserting that Burkina Faso under his rule is instead embroiled in a “progressive, popular revolution”. While the sentiment and ambition of a Sankara-like revolution are evident and welcomed, Traoré’s declaration has raised the eyebrows of his detractors, who suspect that this so-called revolution is little more thana rhetorical smokescreen intended to justify authoritarian control and consolidate political power. Continuing in his speech, he states, “Democracy only has one outcome. We must inevitably go through a revolution, and we are indeed in the midst of a revolution.” Traoré presents the current revolutionary phase — a cover for authoritarian rule — as a necessary yet virtuous duty, postponing true democracy to an uncertain future. If declarations and acts like these — undemocracy and coups — are permitted and unchallenged by the Burkinabé scales of justice, what could Traoré say and do next and get away with?

Oversight 2: Ibrahim Traoré’s strategic alliance with Russia.

Justification: With the rise of Islamist insurgencies in the Sahel starting in 2012, the French government launched Operation Barkhane in 2014 to combat terrorism in the region. Despite the operation’s mixed results, the new junta led by Traoré terminated this agreement with France, accusing it of political interference and complicity with former leader Blaise Compaoré, who was believed to have conspired with Paris to overthrow Thomas Sankara. By February 2023, all French troops were expelled from Burkina Faso, reflecting the broader “Frexit” trend across the continent. With the withdrawal of French military support, Burkina Faso faced a triple crisis of worsening insecurity, economic stagnation, and diplomatic isolation.

Enter Mother Russia, who, under the allure of Vladimir Putin, appeared to offer solutions to this unholy triptych, beginning with a pledge to send“major and high-performance military equipment and appropriate training” to the country. Putin also followed through with promises of humanitarian and economic assistance, such as shipments of wheat, while Russia’s support has also helped legitimize Traoré’s government and his nationalist agenda. Furthermore, Moscow not only endorsed Burkina Faso’santi-French sentiment but also amplified its claims to sovereignty and strengthened regional solidarity among the juntas of Mali and Niger, which are now united under the Alliance of Sahel States (AES). This alliance has fostered a vision of a self-reliant Sahel, free from Western control, and has inspired hope for an independent Pan-African entity that will“go wherever it needs to go to secure our wealth, because that’s what this is all about. We are victims of our own wealth. It is wealth that the imperialists want to take back at any cost and keep us in slavery”.

Forging alliances in power: Vladimir Putin meets Ibrahim Traoré in the Kremlin on the eve of Moscow’s Victory Day Parade, 8 July 2024. Photo by Sergey Bobylev.

Truth: “He who eats another man’s food will dance to his tune.” This Mandinka proverb aptly captures the murky intentions behind Russia’s alliance with Burkina Faso, highlighting the self-interest that lurks beneath a gracious façade. Similarly, the Mossi proverb, “The mouth that invites you to eat has already counted your share,” reflects my initial naïveté in believing in Putin’s generosity. In hindsight, I failed to recognize the irony of Traoré aligning with Putin’s Russia while simultaneously expelling neo-colonialist France. In reality, Russia has merely stepped into France’s old shoes, fostering exploitative resource deals that deepen economic dependency, creating infrastructure and energy projects that tie Burkina Faso to Moscow’s technology and financing, and positioning Burkina Faso as a regional proxy to advance its geopolitical agenda. Effectively, Traoré has willingly traded one form of foreign domination for another, swapping the blue-white-red of France for the white-blue-red of Russia.

Another consequence of this alliance that I did not foresee is the question of Putin’s military support: Who would be sent to assist with the insurgency in Burkina Faso? Would it be the Russian Armed Forces or the Russian National Guard? When Putin pledged “military aid,” what this actually meant was the unleashing of his privately owned war dogs to continue his neo-imperialist ambitions. Since 2022, the Wagner Group — now operating as Africa Corps — has gained privileged access to gold, oil, and other extractive resources through security-for-resource deals organized by the Russian government. The group’s “protection” of citizens from Islamist insurgents is no more than a decoy to safeguard the mines that Russia wishes to exploit for profit. After securing these sites through force, Wagner/Africa Corps exports the resources using shell companies, routing the product through brokers to international markets. The “cleaned” money is then funneled back into Putin’s war machine, marking the end of a sinister and destructive route that the Burkinabé people have paid the price for. Moreover, Traoré’s reliance on Russian-linked paramilitary forces has entangled Burkina Faso in conflicts far from its borders. Burkina Faso’s indirect involvement in Russia’s war in Ukraine is clear, having severed diplomatic ties with Kyiv and accused Ukraine of supporting terrorism in the Sahel.

To top it all off, Russia has launched a massive disinformation campaign across Burkina Faso and the Sahel, creating a digital mirage that blurs the lines between reality and fiction. Central to this campaign is absurdist, AI-generated “slopaganda” — videos that often feature Traoré alongside celebrities or political leaders ostensibly singing his praises. Beneath their playful veneer, these videos carry serious consequences: they warp reality, cultivate a cult of personality around Traoré, and propagate a pro-Russian narrative designed to advance Moscow’s agenda — an influence that ultimately threatens Burkina Faso’s autonomy and well-being.

An example of “slopaganda”: GIF created from “Eminem & Rihanna — God Protect Ibrahim Traoré, Protect Burkina Faso | New Song June 2025” by Harmonia AI.

Oversight 3: Accusations of human rights abuses and crushing dissent

Justification: In a largely post-truth world, distinguishing between what is real and what is not is challenging, especially regarding accusations made in the lawless realm of the internet. Claims of conscripting critics opposing Traoré’s rule, criminalizing homosexuality, and the MPSR killing Burkinabé civilians in raids against insurgents are just a few of the allegations that merit healthy skepticism. Such headlines from primarily Western news outlets remind me of the long-standing trend of framing Africa — particularly francophone Africa — as violent, chaotic, and incapable of self-governance. This pattern felt all too familiar, echoing colonial rhetoric and French neo-colonial influence to discredit a young Pan-African revolutionary striving to achieve significant change. I wanted to resist falling into these repetitive narratives and instead view Burkina Faso through the lens of its history of colonization and its ongoing struggle for sovereignty, rather than through a Western perspective that often undermines African agency.

This conviction led me instead to seek out local Burkinabé news outlets, independent commentators, and Pan-African media — three sources of journalism covering a broader range of developments, policies, and matters relating to Traoré and his rule rather than relying solely on the usual defaming and sensationalistic headlines (articles titled“The cult of Saint Traoré” and“Burkina Faso’s strongman has gone viral” come to mind). Despite the numerous biases involved with state-run and Pan-African media, exploring these Burkinabé outlets gave me a richer understanding of politics and culture under his government. The subjects covered by these outlets are diverse and engaging — like Peoples Dispatch’s endorsement of Traoré forging a new Pan-African path and RTB News documenting enriching discourses between Traoré and Burkinabé citizens. Essentially, I was much more inclined to read articles and opinion pieces that approach Traoré and his rule from multiple perspectives, rather than from a singular, predominantly negative viewpoint. The world does not operate in absolutes, media du francais!

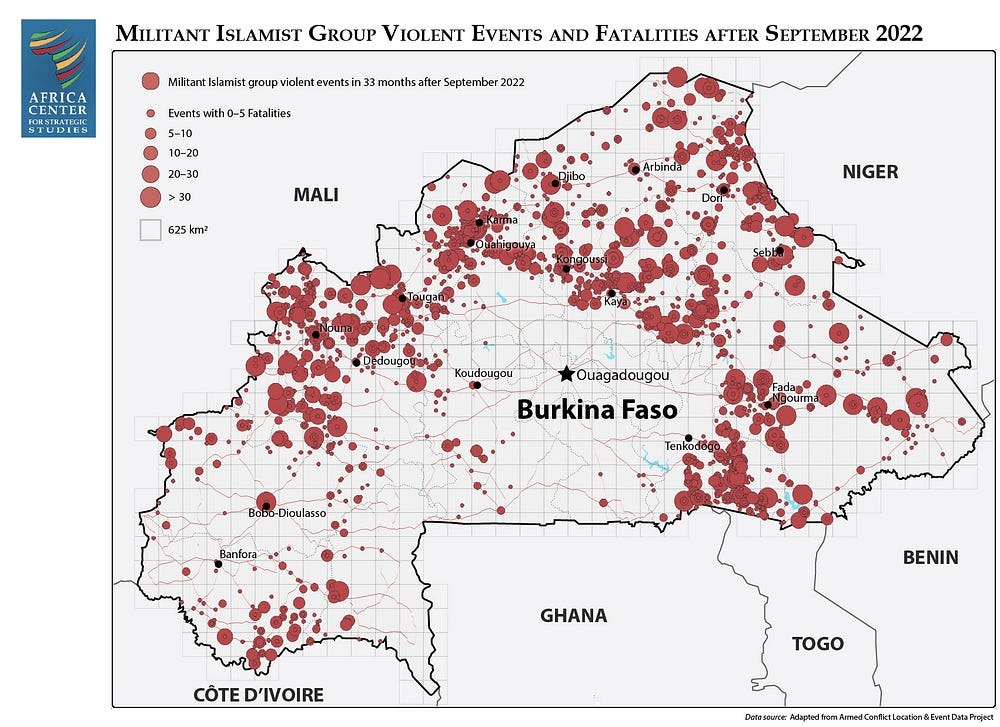

Tracing shadows of conflict: The geographic reach and lethality of JNIM and ISSP attacks across Burkina Faso since Traoré’s coup, 30 September 2022. Map by Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 2025.

Truth: The reality is that I could have read optimistic opinion pieces, PR-driven television appearances, and uncritical news articles about Traoré all I wanted, but I could not ignore the harsh truth about the atrocious acts committed by him and the military groups he has led during his first three years in power. In doing so, it is imperative I admit to the aforementioned Western-linked headlines indeed being true, and that my hesitance to believe and cite them stems primarily from Western media’s indignations towards political African voices past, present, and emerging. Thus, in setting aside my own biases, I decided to scrutinize the various claims of crimes against humanity enacted by Traoré and his posse, symbolizing my awakening from the Traoré trance and a desire to listen to and respect the voices of the afflicted, no matter the political affiliation of the media documenting them.

In 2025, Amnesty International reported that, amid growing insecurity, Burkina Faso’s military junta arrested and forcibly disappeared journalists for reporting on government abuses, dissolved the Journalists Association, and used conscription and intimidation to silence independent media, leaving many journalists in exile or under threat; in 2025, Human Rights Watch reported that on 10 and 11 of March, the Traoré-led Volontaires pour la defense de la patrie (VDP)massacred civilians for purposes of ethnic targeting (primarily of the Muslim Fulani people, who VDP alledge are Islamist collaborators) and intimidation, with dozens of videos capturing the crimes; and in one of his most recent developments, Traoré has alsoformally criminalized homosexuality, making same-sex acts and their promotion punishable by imprisonment, fines, and possible expulsion. These horrific acts have compelled me to question the integrity and humanity of the man responsible for them, making me fearful of future cruelties on this undoubtedly non-exhaustive list. Is this any way to treat human beings? Is this what the ushering in of a “popular and progressive revolution” looks like? In Traoré we trust(?).

Revolutionary or regressive?

For me, it is still too early to determine whether Traoré truly emulates Thomas Sankara and has the capacity to continue his legacy, or if Traoré is just another military puppet for Putin’s neo-imperialist marionette theatre in Africa alongside his Sahelian comrades (more on this speculation in a later piece). There are valid arguments on both sides of the issue, but it’s important to recognize that presenting binary options can overlook the nuance and complexity of Traoré’s political philosophies, beliefs, and character. To effectively assess a leader’s efficacy and legacy, especially considering Traoré’s nascent leadership, one must evaluate them from multiple perspectives and take various factors into account.

For example, in simply critiquing Traoré, one cannot ignore his removal of French as the country’s official language, fostering national pride and emulating Sankara’s own symbolic country name change by encouraging the use of local languages, in this instance, in education and governance. One cannot simply ignore the national development initiatives inaugurated during Traoré’s rule, namely theMoulin Double Star Factory, initiated in 2025, producing over 200 tons of flour daily, creating over 300 jobs, and ensuring food security in the region; or theFaso Mabo Initiative started in 2024, focused on modernizing road infrastructure, improving connectivity across the country, and thus boosting local economies and trade. One also cannot simply ignore Traoré’s nationalization of Burkina Faso’s gold mines and its fostering of self-reliance and boosting of Pan-African confidence by allowing his government to reroute profits back into Burkina Faso’s essential services (even if Russia is getting its unruly cut).

On the contrary, if anyone praises Traoré wholeheartedly they needn’t look further than him withdrawing Burkina Faso from the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2025, an act he justifies by calling the organization“an instrument of neocolonial repression in the hands of imperialism”, but an act nonetheless sure tojeopardize citizen access to justice and redress for crimes against humanity committed by his own junta. If anyone praises Traoré wholeheartedly, direct them to the pervading failures of his junta’s attempts to resolve the insurgency: Islamist attacks surging more than 20%, civilian deaths almost doubling, and over 50% of Burkina Faso territory under JNIM or ISSP control — all since Traoré’s September 2022 coup. And if anyone still praises Traoré wholeheartedly, remind them of his 2025 decision to dissolve the country’s Independent National Electoral Commission, a move that dismantled the body responsible for delaying the return to civilian rule and placing electoral power solely in the hands of the junta.

As you explore the complexities of Ibrahim Traoré’s tenure, you will notice his Wikipedia article growing larger with conflicting accounts of both reform and repression — from promoting local languages and industrial projects to consolidating political authority and sidelining democratic institutions. By now, you might have already formed your own opinion about him, convinced of his ruthlessness or his capacity to lead a just and moral authority with time. Alternatively, perhaps you still need more evidence, curious about the long-term effects of Traoré’s alliance with Russia will be; interested in how he will balance national pride and human rights concerns, and intrigued by whether his authoritarianism will overshadow his progressivism. Regardless of how one judges him, Traoré’s story is still unfolding, and how he navigates the long and difficult road ahead remains to be seen.